On July 24, 1920, Yousef al-Azma, the head of the Syrian Army, lead a regiment of Syria’s army to fight the French at Khan Maysaloun in an attempt to stop the French army from seizing Damascus and taking a Mandate over Syria and Lebanon. He was joined by only part of his army and a rag-tag militia of somewhere between 2,000 — 3,000 people from Damascus and its surroundings.

Statue of Yousuf al-Azma in Damascus

Khan Maysaloun is a rocky, mountainous region about 30 km outside of Damascus. Khan Maysaloun is now called Youssef al-Azma. General Youssef al-Azma was the Minister of War in Syria’s first government under Faisal from 1918-1920. Al-Azma was from a very old and renowned Damascus family. He trained in Istanbul and joined the Ottoman Army before he joined Faisal’s government in September 1918.

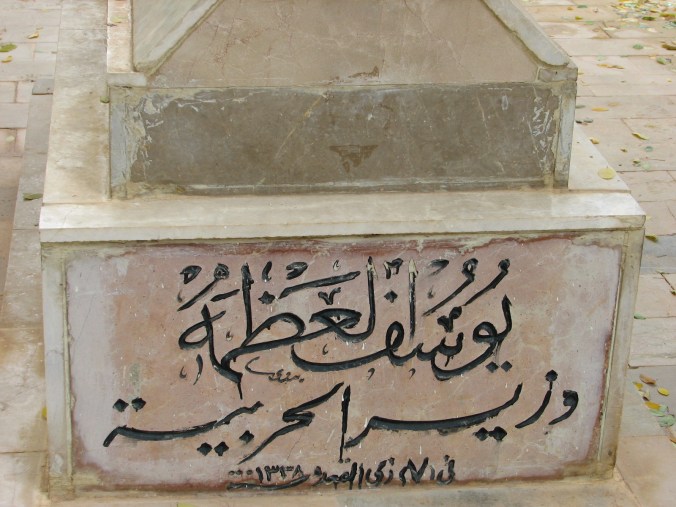

The qibr (tombstone) of Yussuf al-Azma is now located at Khan Maysaloun.

Yousuf al-Azma, Minister of the Army

The story of Khan Maysaloun set in motion a course of events that shaped the modern Middle East. The fact that France was even in a position to march on Damascus in July 1920 happened only through a confluence of events, any one of which could have altered the result. Throughout 1919 and early 1920, the Syrians had managed to keep France from moving south of Aleppo or east of Beirut. The Syrian nationalist militias successfully beat back the French army at every step. But that was only because the French presence in Syria and Lebanon was small, while France fought the Turks in Anatolia.

The Turks had fought France to a standstill in Anatolia by the spring of 1920. The Turks were surrounded by opposing forces of France, Russia and an American-supported Armenia. In the hope of keeping at least the Anatolian peninsula as the territory for modern Turkey, the Turks struck a deal with France — in exchange for Anatolia, Turkey would relinquish its rights in Syria and Lebanon. It was the last wound the Turks would inflict on the Arabs of the Empire.

Still, either the United States or Russia could have intervened to prevent France and Britain both from assuming mandates over the former Ottoman lands in Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Mesopotamia (Iraq). The Russian Orthodox church was very closely aligned with the Syrian Orthodox. However, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 destroyed Russian Emperor and the Russian Orthodox Church along with it. The Yellow King, as the Syrian Orthodox referred to the Russian Empire, was dead.

As part of his peace plan, President Woodrow Wilson promised to recognize the independence of the native peoples of the Ottoman’s Southern Provinces — the Arab world, now called the Middle East. Liberal democracy flourished as an ideology before and after the war in the lands formerly dominated by the great empires, particularly in the Arab world. Wilson established a commission to take a poll of the opinions of the peoples in Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Mesopotamia in the summer of 1919 — referred to at the time as the American Commission, then later the Crane-King Commission, and is now called the King-Crane Commission, since Professor Charles King of Oberlin College lead the mission and now Oberlin College houses its materials.

The Treaty of Versailles was directly connected to the League of Nations. Although the Treaty of Versailles was intended to settle only the disputes between the warring nations of Europe, in order to implement the treaty, in particular the reparations owed by Germany, the Europeans had to convene a League of Nations summit. They did so in April 1920.

President Wilson worked tirelessly not only to negotiate the Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations, but for ratification of the treaty and the League of Nations Covenant in the US Senate. He worked so hard, in fact, that he was felled by a serious stroke in the fall of 1919, which he kept secret for his remaining term as President. The Senate refused to ratify the Treaty, because of Article X of the League of Nations Covenant, which the Senate feared violated US’ sovereignty.

At the same time, there was no one to receive the Report of the American Commission, which showed that the people of the Near East were greatly opposed to mandates by France and Britain, and also opposed to Jewish immigration to Palestine from Russia and Europe. Since before the War, Jewish emigration from Europe and Russia to Palestine dramatically increased property values in Palestine and drove out many Palestinian farmers. The Crane-King Commission report, like the Treaty of Versailles, arrived in America DOA. And, like Wilson’s stroke, the Crane-King Report was kept secret until 1932.

As a result, the Entente Powers who won the Great War convened a League of Nations summit in April 1920 without the moderating influence of President Wilson. They granted themselves a mandates over Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Mesopotamia and received Turkey’s acquiescence in their ambitions.

The Syrians responded in kind — the Syrian Congress convened, declared independence and named Faisal as the King of Syria.

Faisal at his very-lightly-attended coronation ceremony as King of Syria in April 1920.

On Bastille Day 1920, France’s General Gouraud gave Faisal an ultimatum — allow France to take control of Damascus, prosecute those who resisted the French Mandate, accept French as the national language and the Franc as the national currency, or he would move his army out of Western Zone, essentially Beirut, and invade the East Zone, the rest of Syria. Gouraud sought not a mandatory power over Syria and Lebanon, but complete submission to and capitulation by France. Instead of istaqlal taam, complete independence, the Syrians faced istuwla taam, complete occupation. Gouraud gave Faisal 48 hours to accept his demands. The Syrian cabinet asked for an extension of time to respond. The members of the cabinet debated refusing the ultimatum, but feared doing so would only bring more suffering on the Syrian people. Faisal acquiesced to Gouraud’s demands on July 18, 1920, on the condition that the French army would remain encamped near Beirut and not march on Damascus.

Gouraud refused to accept Faisal’s terms and marched on Damascus. Gouraud had history in mind — he wanted to be the only general in the history of human civilization to march triumphantly into Damascus, and in doing so obtain France’s revenge for the Battle of Hittin, when Salah a-Din slaughtered the Knights Hospitalers ending the Crusades.

As Faisal’s cabinet and much of the Syrian army fled Damascus, Yousuf al-Azma and a group of soldiers encamped at Khan Maysaloun with the intention of confronting the French army and buying Faisal as much time as possible to negotiate with Gouraud. When al-Azma left Damascus for Khan Maysaloun he asked his friend and fellow cabinet member, Sati al-Husri, to take care of his wife and daughter. He knew he was going to war for the last time.

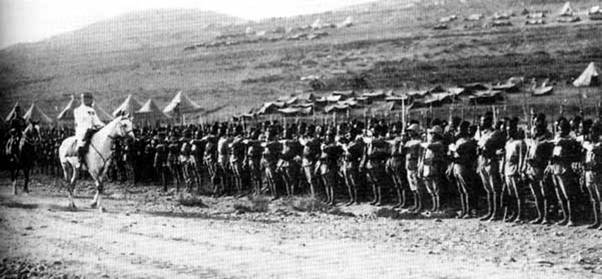

Al-Azma and the remains of the Syrian army were joined by a rag-tag militia of 2,000 – 3,000 Damascenes who took the train from Baramki Station in Damascus to Khan Maysaloun, carrying their own weapons — rifles, pistols, swords, bats, etc. The problem — al-Azma and his militia had about 12,000 rounds of ammunition and almost no artillery. They faced a French army with heavily armed Senegalese footmen backed by heavy artillery and an elevated fighting position. The French even had air support, which surveyed the march from Damascus to Khan Maysaloun on the morning of July 24, 1920.

Led by General Mariano Goybet, the French army let the Syrian army exhaust its ammunition before attacking from their advanced position in the hills overlooking Khan Maysaloun. A gatling gun fixed on al-Azma’s position and killed the general and the men around him. The battle, which began at sunrise, was over by 10 a.m.

Gen. Mariano Goybet overlooking his troops at Khan Maysaloun.

Two days later, General Gouraud drove a car triumphantly into Damascus, accomplishing what the Franks were not able to accomplish during the Crusades. As the story goes, General Gouraud drove straight to Al Aqsa Mosque, where Salah a-Din is entombed, and walked up to Salah a-Din’s tomb, kicked it and said, “Reveillez-vous, Salah a-Din. Nous sommes retournes.” Awake Salah a-Din! We have returned.

If you have read this far, perhaps you can imagine that in this strange confluence of historic events that shaped the modern Middle East, there are a myriad of interesting stories, any one of which would be good material for a historical novel. The Peddler is one of them.